C is for… Cathedral

St Paul’s Cathedral

London is a city of many wonders, and amongst them certainly count its many churches: in total, the city has over 2,000 of them. Standing proud amongst this host is the most magnificent of them all – St Paul’s Cathedral. Set atop Ludgate Hill, the highest point in the ancient City of London, it dominates the skyline and the views across the river from the Southbank. Built at the turn of the 1700s, it was the tallest building in London right up until 1963, when the city’s first skyscraper was built at Millbank, just along the river from the Tate Britain art gallery.

Although this particular version of St Paul’s Cathedral is a little over 300 years old, there has been a Christian church on that site for much longer. The first recorded cathedral of St Paul in London was built in the year 604, giving it a history stretching back over 1,400 years. This early church was founded by Mellitus, Bishop of London; he was sent by Saint Augustine to convert the king of the East Saxons to Christianity. However, in 616 AD the king, Sæberht, died, and the local people reverted to paganism. At some point between then and the late 7th century, the church building was lost; thus ended St Paul’s Version 1.

When Christianity was re-established in the region in the late 600s, a new cathedral was built, where several Bishops of London were buried; this one fared much better, lasting almost 300 years, until in in 962 in burned down. Thus ended St Paul’s Version 2, although this is not the last we will hear of fires and St Paul’s.

The third incarnation of the church survived only a little over a century, and in 1087, it once again succumbed to fire.

At this point, in the late 11th century, a major cultural change had taken place in England: for in 1066, we had been invaded by the Norman king William the Conqueror. He brought with him many ideas, including a penchant for building the most important sites in stone; previously, almost all of London would have been low two- or three-storey structures of timber and thatch – hence the prevalence of fires.

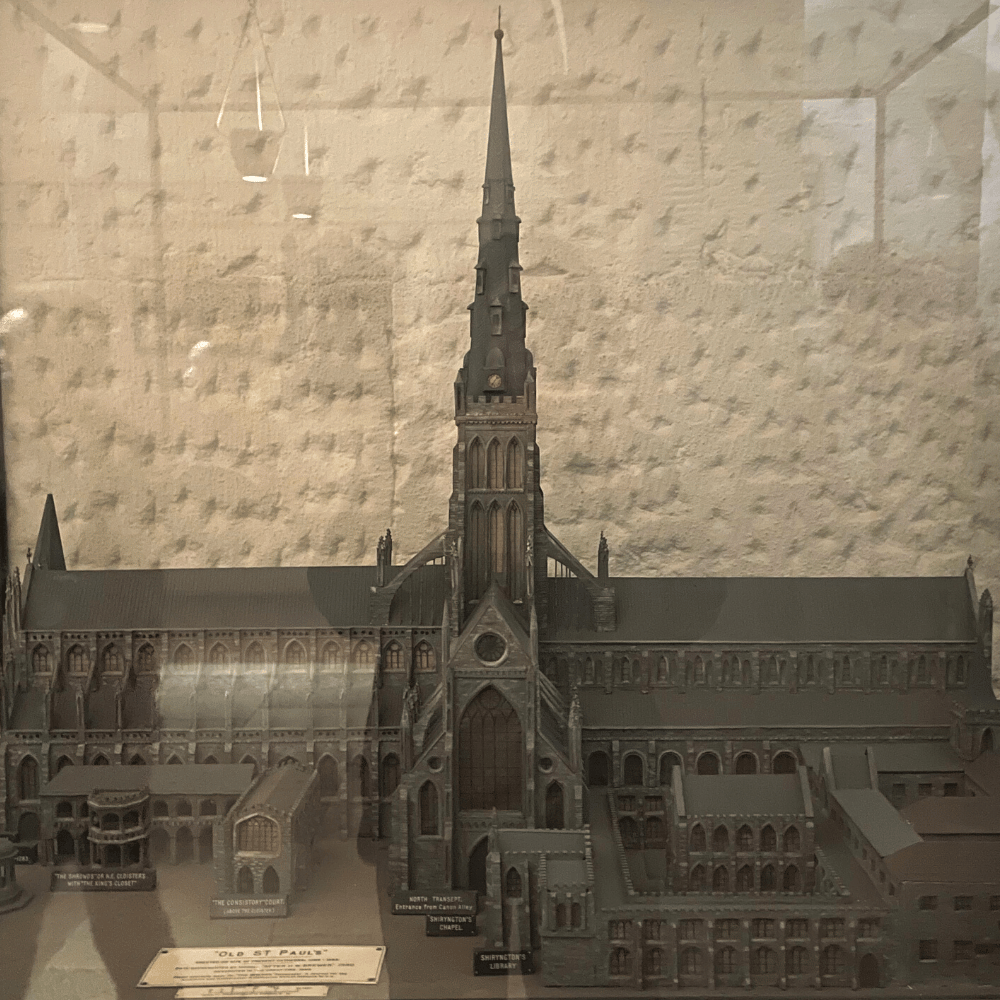

Model of Old St Paul’s

And so, after the burning down of St Paul’s Version 3, the Normans began construction on the grandest cathedral yet seen in London – indeed, it is believed that this fourth version of St Paul’s had the tallest spire in the whole of Europe when it was built. It took around 150 years to complete, being consecrated in 1240, and was magnificent: its spire was around 500 feet high, and the church itself was almost 600 feet long – around 60 feet longer than even today’s imposing building.

It was one of the two most important churches in London – the other being Westminster Abbey – and was the site of many historic events, including the wedding, in 1501, of the young princess Katherine of Aragon to the English king-in-waiting, Arthur.

This huge church lasted many centuries, until in September 1666 London suffered one of its worst ever catastrophes: the Great Fire of London. This devastating blaze destroyed around 80% of the city, including Old St Paul’s. We will hear more about the fire and its effects in the “F” blog on Fire.

A contemporary painting of the Great Fire of London burning Old St Paul’s. Source: Wikimedia

In the wake of the fire, the great architect Sir Christopher Wren was commissioned to build a replacement, even grander and more magnificent than the one that had been destroyed. Because of the immense significance of St Paul’s, he was given access to the best craftsmen of the age, as well as plentiful funding from church and state, and so was able to complete his magnum opus in just 37 years. This was an unheard-of achievement in Cathedral building of this era, and quiet astonishing considering the size, complexity, and beauty of Wren’s design.

The interior of the Dome with paintings by James Thornhill

One of the most striking features of the current cathedral is its huge central dome: at over 30 metres in diameter, it was one of the largest in the world when it was built, and it employs some very clever engineering to achieve its great size. The outer, large dome is relatively lightweight, and is supported below by a very strong cone of bricks, which is hidden from view. Below that, the interior painted dome is a very clever design that appears much deeper than it is, giving the illusion that we are looking straight up into the magnificent structure that can be seen from outside. Wren commissioned the artist Sir James Thornhill to paint the dome in the trompe l’oeil style, to achieve this effect.

The marble floor beneath the dome

Below the dome is a beautiful design of coloured marble shapes radiating from a central circle, and around that circle is written an inscription in Latin celebrating Sir Christopher Wren. His tomb is a very simple one in the crypt, and it also bears the same inscription: Lector si monumentum requiris, circumspice - “Reader, if you seek his monument, look around”.

Mosaic of angels

Other treasures of the church include the fabulous Venetian glass mosaics that adorn the lower parts of the dome, the quire, and the space above the High Altar. These were added much later, in the 19th century, as apparently Queen Victoria felt that the calm white and grey church was “dreary and dingy”, and wanted to add some colour and glitz.

The High Altar itself is a close cousin to the one at St Peter’s in Rome, with beautiful barley twist columns and a decorative roof, or baldocchino, above.

Funerary monument to Frederick Leighton, painter and sculptor

The final treasures of St Paul’s are its great funerary monuments and tombs.

In the crypt, near to the tomb of Christopher Wren himself, lie artists such as Joshua Reynolds, founder of the Royal Academy, and Frederick Leighton, one of Queen Victoria’s favourite artists; like the Duke of Wellington, he also has a memorial in the main nave above.

Near to them is also the Chapel of St Faith, better known as the OBE Chapel: this is the spiritual home of the Order of the British Empire, whose members include such well-known people as Sir Elton John, Dame Judi Dench, and Sir Mick Jagger (although Keith Richards, his fellow Rolling Stone, turned down the offer of a similar honour).

The OBE Chapel

The cathedral is also the final resting place of many military heroes: in the main nave you find the immense memorial to Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. His tomb is in the crypt below, not far from that of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, who also defeated Napoleon, at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Around them are memorials to many other military and naval heroes, as well as to those associated with war, such as Florence Nightingale, the nursing pioneer who tended soldiers’ wounds during the Crimean War.

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson’s tomb

There are many other wonderful details and fascinating stories associated with the cathedral: if you would like to know more, contact me to book a special tour of St Paul’s.